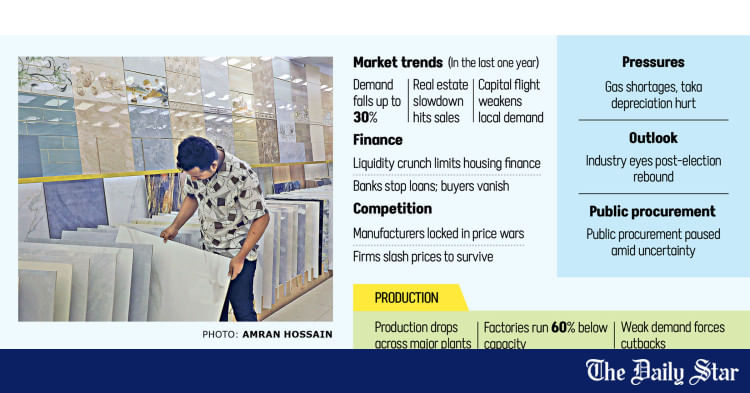

Bangladesh’s ceramic industry is going through its harshest downturn in more than 10 years, with demand for tiles and sanitaryware collapsing by as much as 30 percent, according to industry insiders.

The slump, driven by a prolonged stagnation in the real estate sector, a freeze on government development projects, and a liquidity crunch in the banking system, has pushed many smaller manufacturers to the brink.

Industry insiders say the crisis has been further intensified by capital flight, inflation and energy disruptions, ultimately triggering destructive price wars and leaving the sector trapped in a spiral of falling demand and rising costs.

According to the Bangladesh Ceramic Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BCMEA), the country has 62 ceramic companies, including 11 tableware, 12 sanitaryware, and 39 tile manufacturers. Together, they have a combined annual production capacity of 207 million square metres of tiles, 32 million pieces of tableware, and 1.6 crore pieces of sanitaryware.

Local manufacturers meet 87.29 percent of domestic demand, which has been growing at an average annual rate of 12.71 percent. Domestic consumption stands at around $633 million for tiles, $180 million for sanitaryware, and $75 million for tableware.

REAL ESTATE SLUMP AT THE ROOT

“The ceramic sector has entered a deep slump,” said Md Mamunur Rashid, additional managing director of X Ceramic Group. “Real estate has seen almost no growth in recent years, and because our industry is directly tied to it, the impact has been severe.”

He also blamed the banking sector crisis, driven by rising non-performing loans and large-scale capital flight during the previous administration, for choking off credit to potential homebuyers.

“Banks once financed 70-80 percent of apartment purchases. That has stopped. Middle-income professionals can no longer afford flats, and even upper-middle-class buyers are moving money abroad instead of investing locally,” Rashid explained.

Tiles have been hit hardest, with demand plummeting by 25-30 percent over the past two years.

With factories operating at full capacity, producers have been forced into survival mode, selling below cost and offering higher commissions to dealers to keep products moving.

“It has created a brutal price war. Everyone is cutting prices, offering higher dealer commissions just to stay afloat,” Rashid said.

If the crisis prolongs, smaller firms are at risk of going out of business.

“Large groups like Akij or DBL can manage losses through diversification. But smaller, tile-only firms may not survive,” he warned. “Without skilled management and resources, many will shut down or be absorbed.”

Mohammad Khourshed Alam, chief operating officer of Akij Bashir Group, said construction material demand has dropped by 25 percent. “Across all product lines, especially construction, demand has fallen sharply. We’ve scaled back production to 70 percent of capacity.”

Akij Ceramic, a unit of the group, can produce 65,000 square metres of tiles a day but is now running nearly 30 percent below that capacity. “We are caught in a price compression cycle. Costs are climbing, but we can’t pass them on to consumers. Prices remain flat despite inflation.”

Their sanitaryware segment is also under pressure. Government clients normally account for around 30 percent of sanitaryware demand, but those agencies have paused procurement. Only private construction in rural areas is offering some support.

Alam believes that a real recovery will depend on political stability and a resumption of government spending following the next election cycle.

Mir Ceramic Ltd, another leading player, has also scaled back.

The company’s Deputy Managing Director, Ruslan Nasir, said the industry had been struggling for three years, but the suspension of public development projects by the interim government had dealt a particularly heavy blow.

“As the government is one of the largest consumers of ceramic products, its absence from the market has had a massive impact,” he said.

In addition to demand-side challenges, the sector is also grappling with the depreciation of the taka, high interest rates, and gas shortages — all of which have pushed production costs higher, despite the industry’s role as an import-substitute sector.

“Until a stable, elected government takes office and resumes public investment, we don’t foresee a meaningful rebound,” Nasir added.